Glaciers Are Solid Rivers

- A glacier is a large accumulation of many years of snow, transformed into ice. This solid crystalline material deforms (changes) and moves.

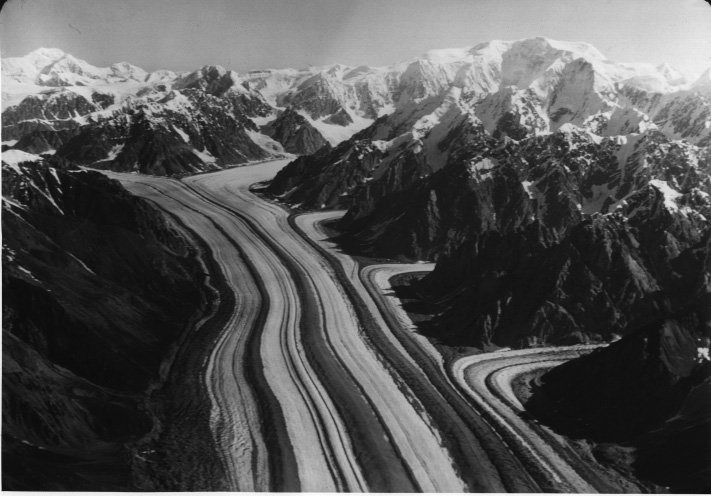

- Glaciers, also known as “rivers of ice,” actually flow. Gravity is the cause of glacier motion; the ice slowly flows and deforms (changes) in response to gravity.

- A glacier molds itself to the land and also molds the land as it creeps down the valley. Many glaciers slide on their beds, which enables them to move faster.

- Rock that falls onto the glacier’s surface is incorporated into the glacier and erodes the bed, forming sediment. The glacier and its load of rock debris flow down-valley.

- A glacier discharges snow from its accumulation area in the same way a stream discharges water from its watershed.

- Sometimes, in cold climates with a lot of snow, like Alaska, glaciers flow all the way down to sea level. These glaciers carve fjords and make icebergs.

- At the glacier’s face, ice which has been melting, fracturing, and has been battered by the sea breaks off as icebergs – a process, called calving, that balances the flow of ice from behind.

Glacier Advance and Retreat

Glaciers advance and retreat. If more snow and ice are added than are lost through melting, calving, or evaporation, glaciers will advance. If less snow and ice are added than are lost, glaciers will retreat.

Accumulation Zone: Where snow is added to the glacier and begins to turn to ice – Input Zone

In this zone, the glacier gains snow and ice.

- This is the upper region of the glacier.

- Water seeps through accumulated snow and gradually forms horizontal “ice lenses” and vertical “glands.”

- Eventually, the whole mass compresses into a deep bed of dense ice.

- The ice flows like a conveyor belt driven by gravity and ever mounting snows.

Ablation Zone: Where the glacier loses ice through melting, calving, and evaporation – Output Zone

In this zone, the glacier loses ice.

- This is the lower region of the glacier.

- Meltwater flows out to the terminus through hidden channels and tunnels.

- Oldest ice is the deepest.

Equilibrium Line: An equilibrium line divides the two areas. This spot is like an old-fashioned pair of scales used to weigh gold dust.

- If the glacier’s scale, or budget, is balanced with enough new ice added to replace the loss, the glacier is stable, with little advance or retreat.

- If the balance is tipped, the glacier shifts and either advances or retreats.

Motion and Movement

Mass Balance: The difference between the amount of material that a glacier accumulates and the amount lost during ablation is called its mass balance. The equilibrium line moves down (1) or up (2) a glacier as the mass balance changes.

- Gains more than it loses = positive mass balance

- Loses more than it gains = negative mass balance

Ice Flow: Glaciers move by internal deformation (changing due to pressure or stress) and sliding at the base. Also, the ice in the middle of a glacier actually flows faster than the ice along the sides of a glacier as shown by the rocks in this illustration (right).

Glacier Bed: Glaciers move by sliding over bedrock or underlying gravel and rock debris. With the increased pressure in the glacier because of the weight, the individual ice grains slide past one another and the ice moves slowly downhill. The sliding of the glacier over its bed is called the basal slip. Water lubrication is crucial to either process.

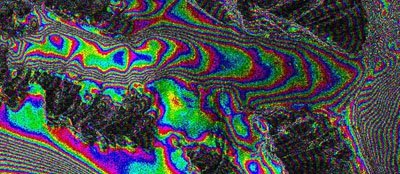

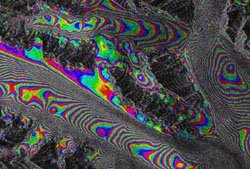

Revealed by Satellite Radar

These images allow glaciologists to study in very fine detail the way in which glacier ice flows downhill. An “interferogram” is an image made from the comparison of two radar satellite scenes of a glacier. The cycle, or repeating, color patterns represent an overlaying of information about surface elevation (like topographic maps) with information about how fast the surface of the glacier is moving.

The glaciers in the images are part of the Bagley Icefield in Southcentral Alaska. On the mountains (which are stationary), the color bands represent increasing elevation. On the glacier surface the color bands primarily represent surface speed.

In these images the color bands are like a series of parallel moving sidewalks, each moving slightly faster than its neighbor as one traverses from the edge of the glacier towards the center, so that the ice in the middle is moving the fastest.

Moraine: Moraines are mounds, ridges, or other distinct accumulations of unsorted, unlayered mixtures of clay, silt, sand, gravel, and boulders. There are many types of moraines:

- Terminal or toehold – The advancing ice scrapes and grinds the bedrock boulders and gravel beneath it and pushes ahead of itself a ridge or terminal moraine of rock and earth. A terminal moraine helps to anchor the glacier’s ice.

- Lateral – their rock material comes from the valley walls.

- Medial – When two lateral moraines combine, or a tributary glacier joins the main flow, they form a single medial moraine, which extends as a long, dark stripe down the middle of the glacier towards the snout. When medial moraines come close to one another near the terminus, a glacier may look multicolored or striped. Medial moraines can create interesting swirls and loops.

- Ablation – an accumulation of melted-out rocks (sometimes just sparse collections of glacial till).

- End and Push – created near the margin of a glacier, at the terminus.

- Ground and Dump – glaciers often dump out their supply of rocks as they retreat.

Terminus: The terminus is the lowest end of a glacier. Also called the snout, toe, or leading edge. Near the terminus, the glacier’s surface thins and stretches and breaks into a mosaic of crevasses. Below, the terminus of Hubbard Glacier in Alaska is shown as a large chunk of it is breaking off (also called, “calving”).

Meltwater flows through hidden channels and tunnels, reaching the base of the ice to lubricate its flow, and pours from under its face in a silt-laden cloud.

Nunatak is an Inuit term for an island of bedrock or mountain projecting above the surface of an ice sheet, highland icefield, or mountain glacier. The glacier flow has gone around the bedrock, leaving behind this distinct geologic feature.

Scientists use stakes to measure glacier movement. In the picture to the right below, the glacial stream velocity is being measured by a scientist.

Glaciers advance and retreat in response to changes in climate. As long as a glacier accumulates more snow and ice than it melts or calves, it will advance.

How do Glaciers Move?

Vocabulary Plus!

accumulation zone

debris

watershed

discharge

ablation zone

equilibrium line

mass balance

deformation

calving

crampons

crevasse probe

tributary

moraine

terminal

lateral

medial

glacier bed

basal slip

terminus

meltwater

rope

gravity

Review Questions

(some of the answers may come from the vocabulary list)

- What causes the glacier to be in motion?

- True or False: Glaciers slide on their beds and this enables them to move faster.

- True or False: Glaciers can’t flow down to sea level or carve fjords.

- What is the zone where a glacier gains snow and ice?

- What is the zone where a glacier loses ice through melting and calving?

- What is the difference between the amount of material that a glacier accumulates and the amount it loses during ablation?

- If the glacier gains more than it loses, will the glacier have a positive or negative mass balance?

- True or False: The snout is another name for the terminus on a glacier.

- Name one type of moraine.

Brain Challenge!

When climbing a glacier, if you could only bring one other thing with you besides warm clothes, boots, and a camera, what would you bring?

Exercise: Connect the Words with Definitions

Draw lines to connect the words to their definitions

Ablation zone

Accumulation zone

Calving

Moraine

Equilibrium line

Terminus

lowest end of a glacier

soil and rock debris

equal melting/adding

losing snow

adding snow

ice breaking off

Project: More Silly Putty Cigars

Roll some Silly Putty into a cigar shape to make it look like a glacier. Then grab the ends and pull it slowly apart. See it sag and still stay as one piece. This is like ice. When ice moves slowly, it flows and deforms.

(Courtesy Glaciers of North America, By S. Ferguson)